IRON DEFICIENCY

Iron is an essential element for the body. Living organisms from primitive to more complex life forms need iron to perform many biological reactions including mitochondrial respiration (mitochondria are involved in cellular respiration), cell proliferation and synthesis of proteins such as haemoglobin and myoglobin. Iron levels must therefore be finely regulated by an adequate homeostasis balance to allow cells to use iron while avoiding its harmful effects. Hepcidin, a hormone produced by the liver, is the main regulator of iron homeostasis. Fluctuations in hepcidin levels are closely correlated with serum levels of ferritin.

Iron is the element with the highest concentration in the human body. In a healthy adult human body, there are about 3-4 grams of iron (on average woman have 3 g and man 4 g). 60-70% of iron is contained in haemoglobin, 20-30% is contained in ferritin (protein involved in iron storage), and the rest in myoglobin (protein that carries oxygen to the cardiac and striated muscle cells) and metabolism proteins.

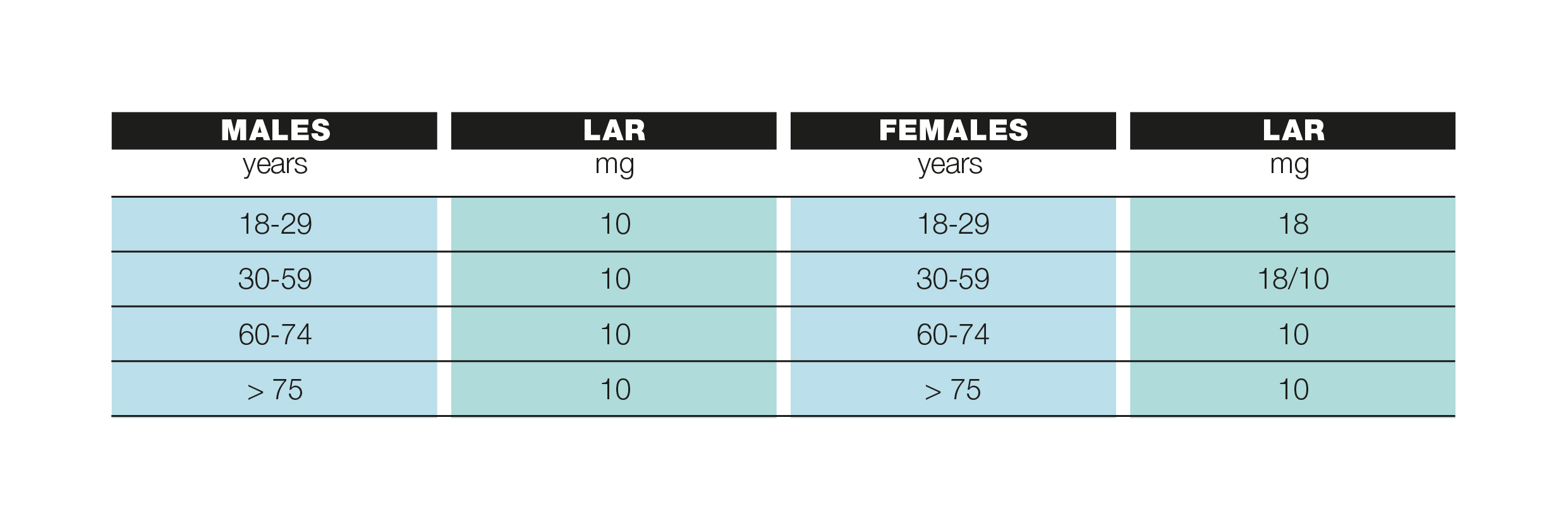

The amount of iron needed by a healthy adult corresponds to about 10 mg per day, while for a healthy woman it is greater (about 15-18 mg). The need for iron is greater in certain periods of life such as childhood, pregnancy, breastfeeding and of course in the case of chronic blood loss. The table summarizes the recommended iron intake levels (LAR) for the adult population according to the LARN (Nutrient and Energy Reference Assumption Levels for the Italian population).

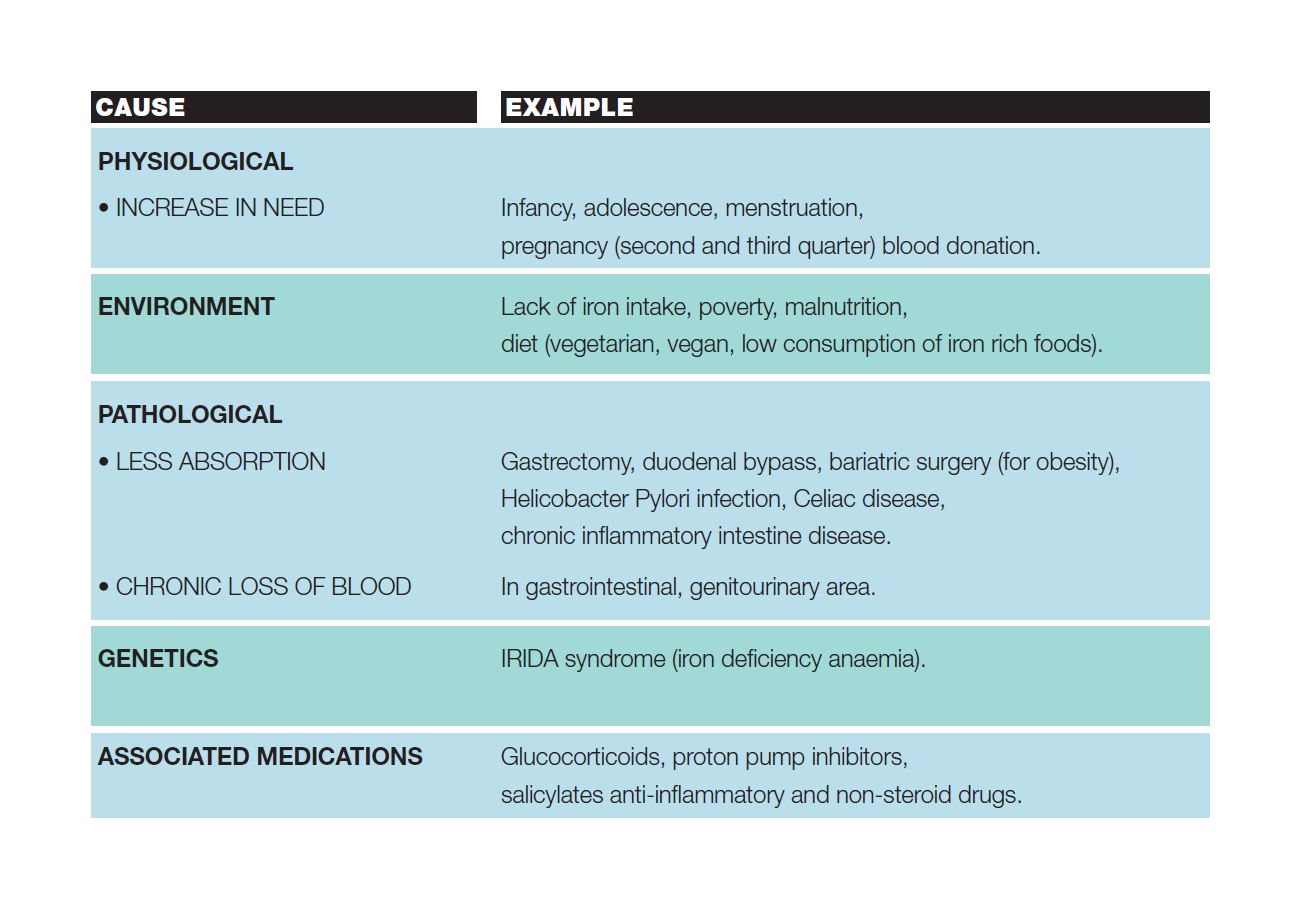

For some people, the risk of iron deficiency is higher and may occur as a result of:

- Increased requirement: pregnancy, breastfeeding, growth and development in adolescents, competitive sports, regular blood donations

- Strong loss of blood: after childbirth, hypermenorrhoea (heavy menstrual bleeding), chronic bleeding (e.g. gastrointestinal tract for esophagitis, inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease, erosive gastritis etc.), haemorrhage after surgery

- Insufficient intake from nutrition: unbalanced diet, vegetarian diet

- Chronic diseases: chronic heart diseases, oncological pathologies, chronic kidney diseases

The table summarizes other causes for iron-poor anemia.

IRON DEFICIENCY SYMPTOMS

We have seen that iron is involved in many processes of the organism: oxygen transport in the blood, muscle activity and protein metabolism. This explains why the symptoms of iron deficiency can be multiple and often nonspecific. The most common symptoms associated with iron deficiency are:

- Asthenia: feeling of tiredness, weakness or lack in energy/strength, easy fatigue and exertional dyspnoea

- Hair loss and brittle nails

- Restless leg syndrome: a disorder that causes an urgent and uncontrollable need to move the legs, often accompanied by “unpleasant feeling in the legs”. Symptoms are relieved by moving the legs

- Impaired thermo-regulation: intolerance to cold. Iron seems to be involved in the body temperature-regulating mechanism

- Headache, angina, cardiac decompensation

- Pallor

- Increased predisposition to infections

What are the biochemical signals of an iron deficiency?

- Serum ferritin value less than 15 mg/dL

- Serum iron (concentration of transport iron in the blood) less than 60 mg/dL.

Iron deficiency can lead to iron-deficiency anaemia. This occurs when, in addition to a lack of ferritin and serum iron, there is also a decrease in haemoglobin levels (values less than 12 gr/dL for women and 14 for men).

Anemia is a very frequent complication in patients suffering from oncological pathologies, both at the time of diagnosis and during therapeutic treatment. The ECAS (European Cancer Anemia Survey) investigated the prevalence, incidence and treatment of anemia in cancer patients. It was observed that 39% of patients had anemia at the time of diagnosis, while 67% developed it during chemotherapy. There are many causes of anemia in patients but for most people, the dominant mechanism is iron deficiency.

Iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia can be treated with existing iron-based drugs that can be administered by mouth or by intravenous injection. Oral iron administration is the most common and makes use of iron salts including iron sulphate, gluconate and fumarate. Therapy may have some side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, constipation and “metallic taste”.

Intravenous administration is more effective than oral therapy and it increases iron and haemoglobin levels more rapidly. Also, this method may cause some side effects such as nausea, vomiting, itching, headaches, myalgia and chest/back pain.

Your doctor will determine whether drug therapy is necessary and, if so, the appropriate route of administration. Keep in mind that proper nutrition can have a positive effect by increasing iron intake and absorption. Proper nutrition does not substitute prescribed drug therapy but can effectively integrate it.

DIETARY IRON

The iron present in the body comes from the dietary intake, which allows us to maintain a balance between absorption and daily losses. After the iron has been absorbed by the intestine, it is distributed to various body compartments for synthesis, storage and transport processes. Since it is not possible to control its elimination, the amount of iron in the body is regulated by controlling its absorption. About 1-2 mg of iron per day is expelled through our skin, gastrointestinal tract and genitourinary tract mucosae exfoliation.

Iron is present in many foods, but the amount of iron that can actually be absorbed and utilized varies according to its source. There are two forms of food iron:

- HEME IRON, also called “animal iron”, is bonded to a molecule of haemoglobin or myoglobin. It makes up about 40% of the iron contained in animal source foods (meat and fish). This type of iron can be easily absorbed (from 20 to 40% is absorbed in healthy subjects).

- NON-HEME IRON, also called “vegetal iron”, is barely absorbed by the organism; it makes up about 60% of the iron in animal tissues and the totality of the iron found in plant foods. The amount of iron that can be absorbed from plants is less than 5% owing to the presence of substances that interfere with the utilization of mineral salts (especially tannins and phytates). This percentage rises to 10-20% if certain substances are present that positively affect absorption as described below. As a result, the absorption of non-heme iron is strongly influenced by the rest of the diet.

IRON IN FOOD

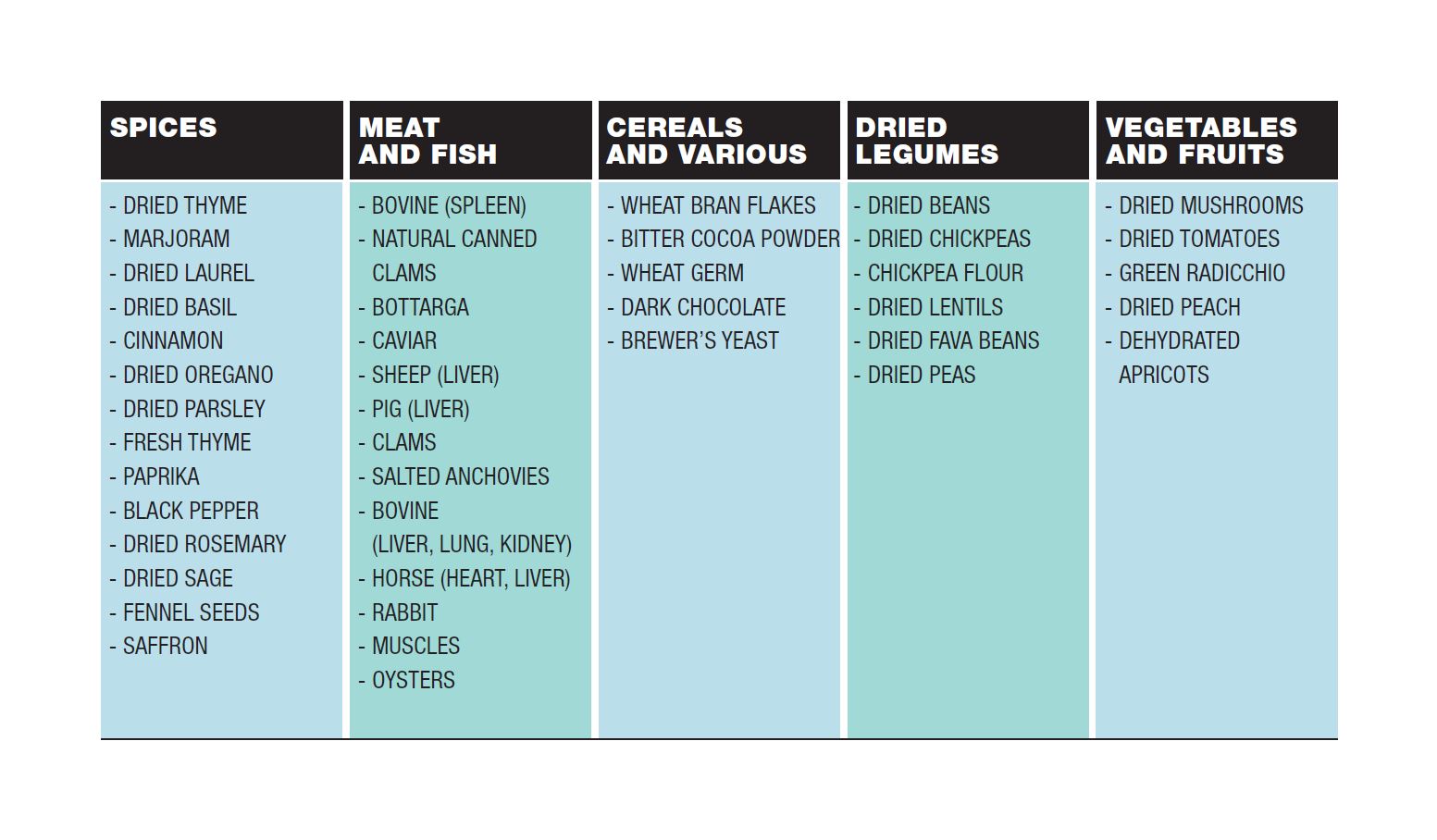

The table lists foods rich in iron and for each group they are listed in descending order, from richest to poorest.

It is a common belief that the best food to ensure a good dose of iron is red meat. In fact, a high iron content is mainly found in bovine, pork and horse liver, spleen, kidney, lung and heart. Some other meats containing good amounts of iron are pheasant (8.1mg/100gr), hare (6.2mg/100gr), and horse (3.1 mg/100gr) meat. White meat e.g. poultry meat contains on average a little less than 1mg of iron per 100g, but it depends on the cut you choose. Muscle tissue such as thigh is richer in iron.

Red meat intake should be limited in accordance with the recommendations of the WCRF (World Cancer Research Fund).

What other sources of iron are there? Clam fish supply a good iron source (14mg/100g) and also muscles and salted anchovies (5.8 and 6.9 mg/100g respectively). Due to their animal origin, these foods contain a good amount of home iron, that can be easily absorbed by the organism. However, be careful not to eat too many clams and mussels as they have a high cholesterol content (50mg/100gr for clams and 121mg/100gr for mussels).

As you can see from the table, many foods containing iron are of plant origin. Vegetal iron is non-heme iron and is barely assimilated by the human organism. As previously illustrated, phytates and tannins interfere with the digestion of food, with metabolic functioning at the gastrointestinal, cerebral or hormonal level. Phytates and tannis also interfer with iron absorption.

Phytates are compounds that capture mineral salts, making them unavailable for absorption, through a chemical mechanism called chelation. Phytates are found in legumes, cereals and cocoa powder. To try to reduce the amount of phytates in food, you should follow some rules. As regards dry legumes, the long soaking of the seeds before cooking, ensures the removal of most of the phytates. It is therefore better to soak the legumes overnight, preferably changing the water at least once or twice. Cooking and skimming off any “foam” that is formed during cooking is another useful method to remove the phytates. For this reason, it is always a good idea to cook legumes for a long time and the same rule can apply to whole grains.

Tannins, polyphenol substances synthesized by plants and contained mainly in the bark are found in tea, coffee, grapes, unripe persimmons and wine. Hence, it is not recommended to drink tea, coffee and wine during a meal of food rich in iron, to prevent these antinutrients from capturing iron and making it insoluble.

Thankfully, there are some substances that can increase iron absorption at the intestinal level. The introduction in the same meal of small amounts of fermented sauces (e.g. homemade sauerkraut or miso), citric acid (lemon), ascorbic acid (vitamin C from vegetables) or even organic acids contained for example in tamari (soy sauce), increases even the absorption of non-heme iron up to 20%.

Herbs and spices are very rich in iron; when dried they contain 30 to 120mg/100g whilst when fresh they contain an average of 10-20 mg/100g. Although eaten in minimal amounts, their constant use can be a valid source of iron. They can be used to season dishes, with the aim of limiting the use of kitchen salt. Another source of iron is brewer’s yeast (4.9mg/100gr) which can be used to season salads or cooked vegetables as an alternative to salt.